I continued to drive North after my encounter with Betty: my destination, Hay River. The three-hour trip was uneventful before I stopped to see Alexandra falls (Hatto deh Naili), part of the Twin Falls Territorial Park. Given how flat northern Alberta is, you would never expect to see a 105-foot waterfall mere meters from the highway. However, the amount of water was staggering and most impressive, its 385-foot span and vertical rocky cliffs to the river below.

As I arrived in Hay River, I did my usual scout of the town, slowly driving through the streets to get a sense of the area; tourist season still needed to begin, and campsites were not open to the public. The town was quiet, a mix of industrial and commercial storefronts separated by the highway. The town was situated on the banks of the Hay river to the East, with Great Slave Lake a couple of kilometres North.

I drove towards the lake, where buildings, homes and industrial real estate were half hiding from view in a mix of thicket and trees; some inhabited and others abandoned. The road turned, and I could see the water between the passing trees from the passenger window every few seconds. Finally, I stopped in a clearing where the lake was in full view. I stretched my legs and walked towards the water's edge. The on-shore winds were bone-chilling cold, forcing me to wear a down jacket. The lake resembled an ocean, white-capped waves pushing large sheets of thick ice ashore due to the spring thaw— the scene void of any land across the open water.

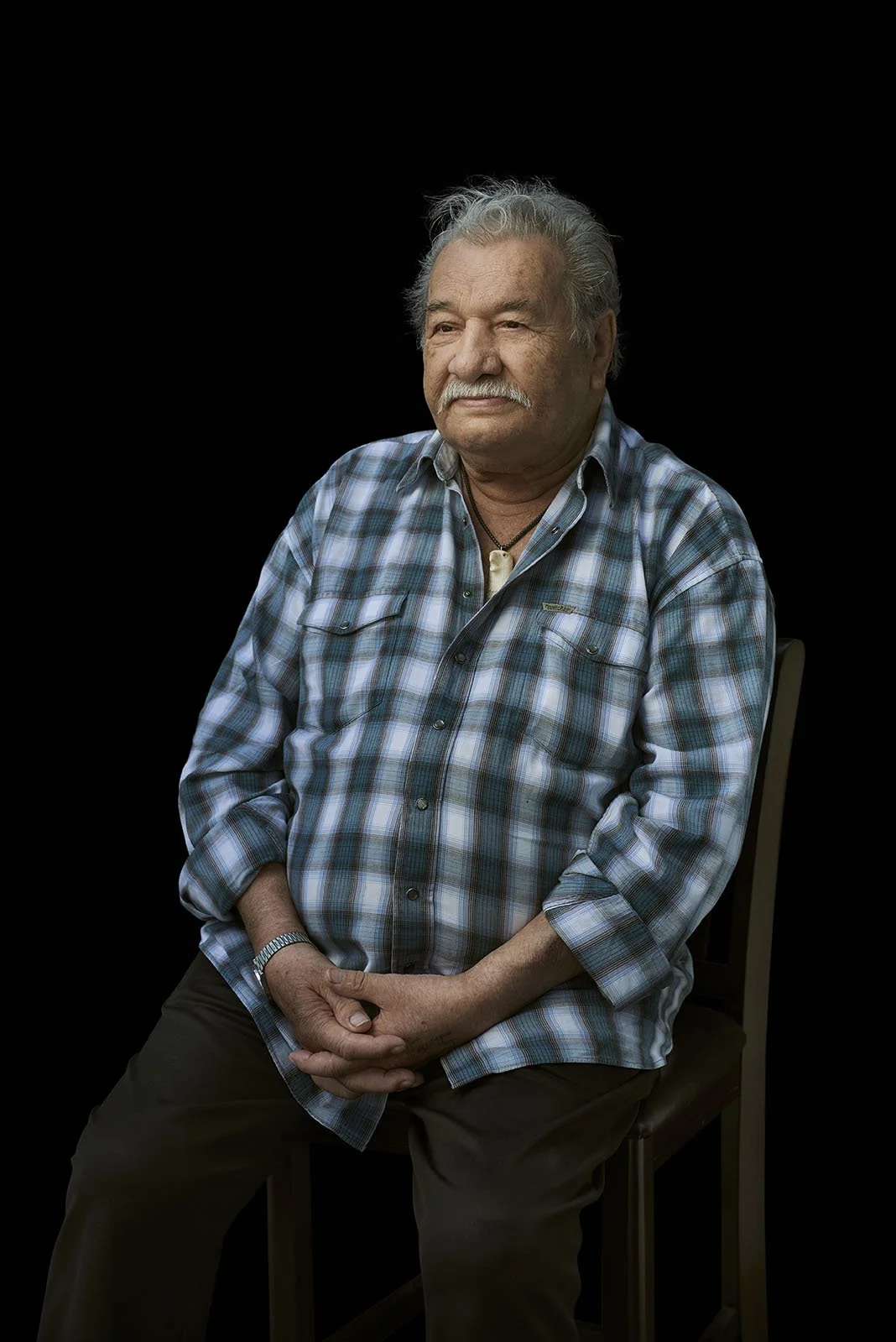

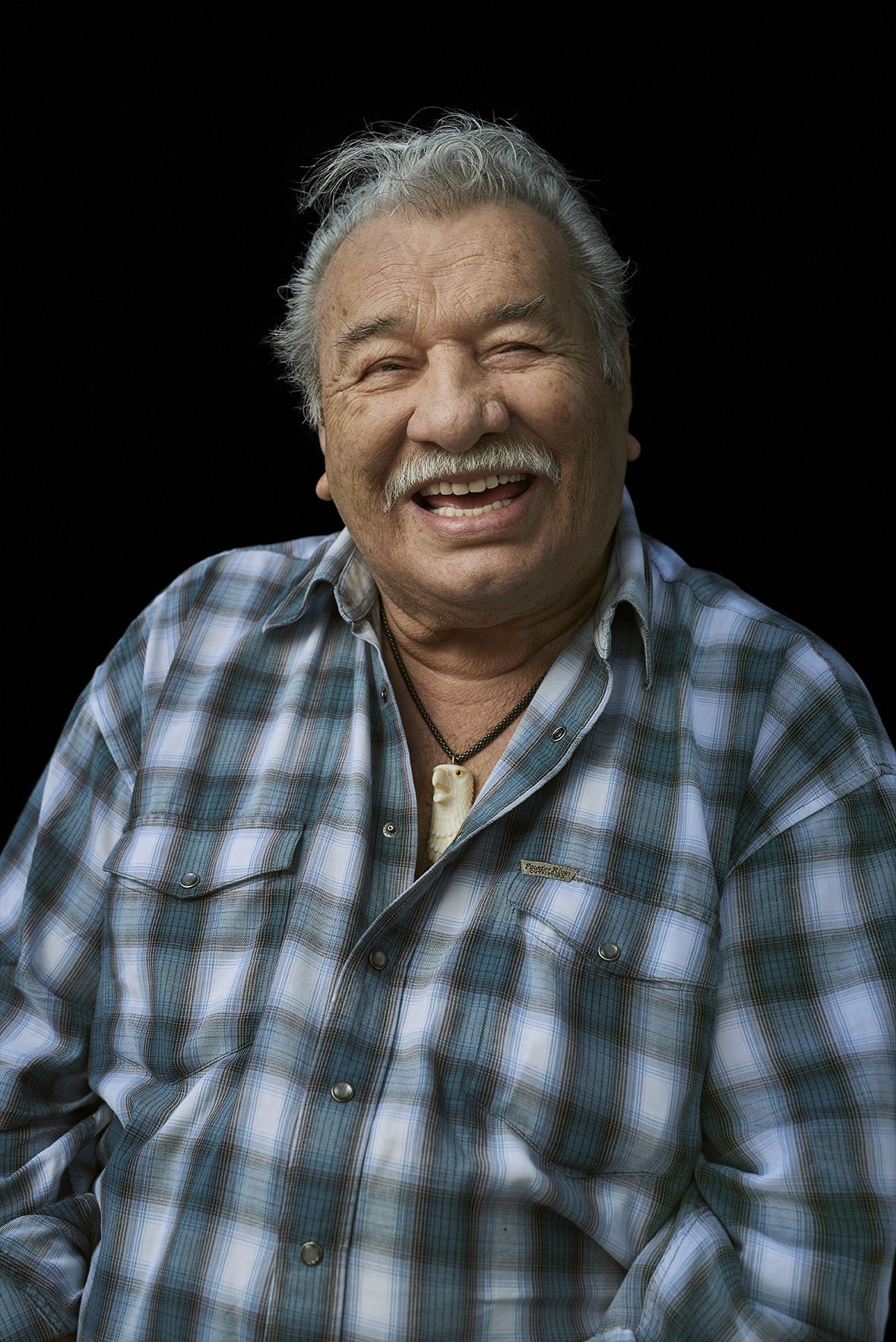

I returned to the town's center to learn more about the locals. After a bit of luck, and a few conversations, I managed a meeting with the mayor the following day, along with a list of phone numbers I was encouraged to call. I found a cafe and started making those phone calls, organizing potential subjects, and gathering more information. One of those contacts was Sonny MacDonald, a local first nations carver who happily agreed to meet me. I invited him to join me for breakfast at the local diner.

I arrived before Sonny, and the diner was everything you would expect in a small town; brewed coffee in weathered medium-sized mugs, the smell of bacon, and a waitress pacing between tables, making her rounds, and referring to customers by their first names. The usual morning crowd gathered, and their banter filled the room. Sonny slowly walked in with a slight limp, cane in hand, refusing assistance from staff or myself. Sonny wasted no time, presenting a stack of albums he brought documenting his life's work and the memories they carried; he was excited to share. Sonny ordered eggs over easy, bacon, tomato and white toast and I, a meat-lover breakfast with tomato and hashbrowns.

Sonny was cheerful and confident, his words spoken with pride. He was born in Fort Chipewyan in 1939 and Metis by birth. He happily bragged with joy that his family lived in one of the original Hudson bay cabins where his mother brought up four boys and three girls, supporting the family by sewing wedding gowns and other items for a living. In 1956, the family moved to Uranium City in Saskatchewan, and Sonny became a heavy equipment operator at the mines. Sonny was seven when he started carving with a pocket knife his father gave him. The knife is called Big Chief and is still in his possession. When he wasn't working at the mines, he carved every day. Unfortunately, he lost his father at a very young age to Appendicitis.

Sonny's carvings started small, making small boats and slingshots and sourcing the material readily available in the forest outside his home. As his skills improved, his work evolved into natural creatures: Arctic graylings, cat tails, and loons. "The carvings pertain to the natural world. You see the natural curvature of the tree and follow that. It's very therapeutic. I go into the wilderness, picking up wood. An artist's mind is very, very imaginative. I don't know what I will crave. When I return, I will throw what I've collected under the workbench until an idea comes to me"... "My preference is a piece of wood with a lot of knots as I like the character. I like to carve cat tails".

We continue to sift through the stack of photos stopping every few minutes from picking at our lukewarm food. The carvings are incredible, some measuring ten to twenty feet in height. As Sonny's career grew, his material list expanded to coral, bronze, granite, and mammoth tusk. "I know an archeologist," he gently brags, followed by a wink. "If we're working on a project with multiple artists, we'll go to the coffee shop and scribble our ideas on a napkin and just go from there." His simplistic approach amuses me. For Sonny, it's just another day as an artist. As the pile of photos dwindled, I noticed a picture of him standing next to Queen Elizabeth II and asked him to explain. "Oh yeah, she was great, and we talked for four minutes. She was interested in the carvings and the process". He then tells me the places he's travelled internationally, the provincial and federal buildings where you can see his work, the private collections and commissions.

When we finished looking through his photos, I asked Sonny if he had anything else to say about his work or life. His response was this, "First and foremost is to trust. Once you've developed that trust between two individuals, that is the best thing that can happen. I cherish good things"... "When you wake up in the morning, stretch out and get the sleet out of your eyes, take your right hand and lift it to the ceiling and pat yourself on your back. You know why?... No one is going to do it for you so you need to do it yourself. Opportunity knocks anywhere and anytime. You have to be an opportunist and put yourself out there".

It is with great sadness that Sonny passed away on April 20th, 2021. It was a pleasure and honour to spend a couple of days with this fine man, and I think of our encounter often.

Rest in peace, Sonny. You are constantly missed.